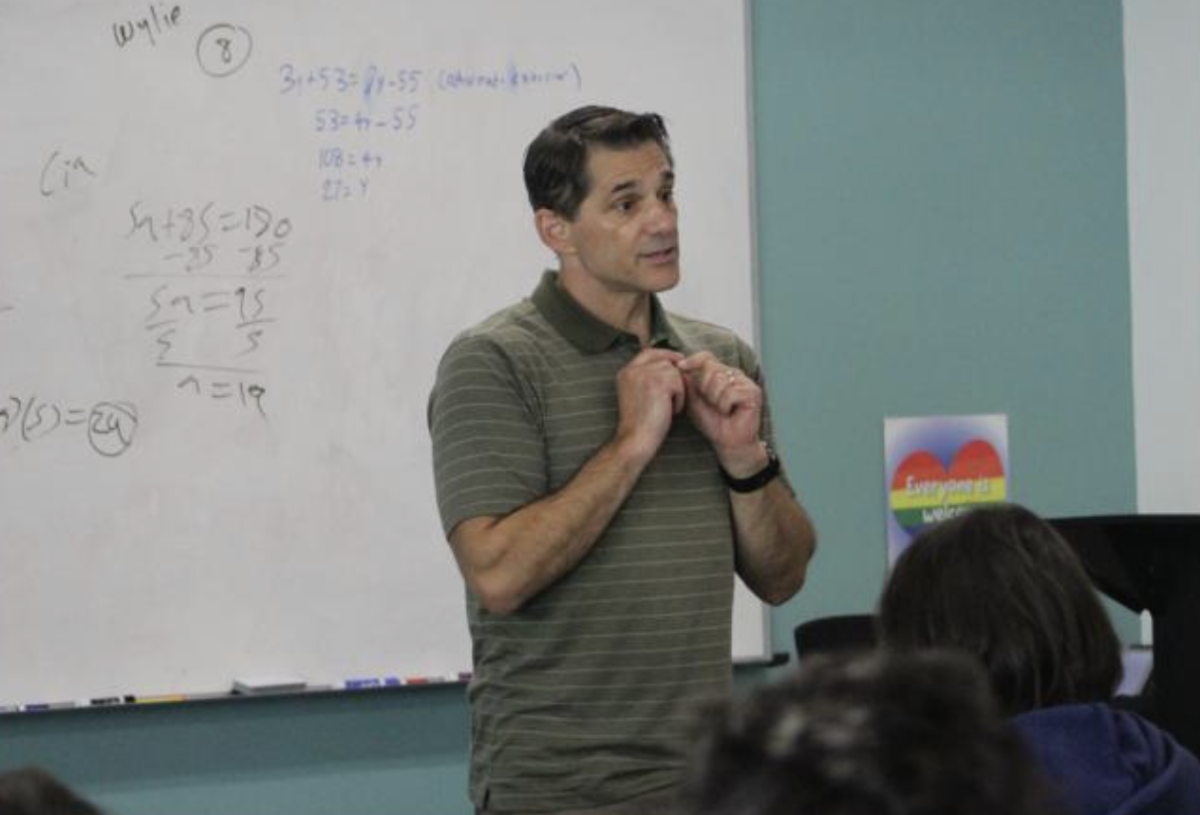

Jason Mills, former CHAI Technology & Ethics teacher, was a teenager in the 90’s, when it was uncommon to be taught tech literacy. The only technology he had growing up was a laptop with a small hard drive. Once he got his laptop he began to question how secure the internet is and what dangers he needed to be aware of. Once his curiosity about cyber security grew, he began helping people in his neighborhood by removing viruses from their computers, while simultaneously learning how cyberattacks occur and how to recover from them. His curiosity about technology, led him to become the CHAI Technology & Ethics teacher helping students learn how to safely use the internet.

As a teenager in the 90’s, Mills transitioned from adolescence to adulthood without footage of himself on social media. He defines tech literacy as understanding where your data goes when you take photos or send messages. Because of the permanence of media today, Mills has always emphasized to his students the importance of knowing where their data goes. He believes that parents should be involved in their child’s internet use, but growing up in different technological eras makes the conversation difficult.

“Students need to understand the permanence of their data,” Mills said. “Because one bad day for a Snapchat employee could be a billion records made public and their private messages could be part of them. Parents need to educate themselves so they can effectively warn their child that the Snapchat photo that times out exists forever.”

According to Taylor Blatchford’s March 2022 article for Family Online Safety Institute, if parents ask their children to teach them how to use technology, parents can come off as interested instead of invasive, making the conversation of tech literacy easier.

Director of Human Development and Parent Education Sarah Huss advises parents to take a friendlier approach than Mills to these conversations so their actions are seen as coming from a place of interest instead of control. She recognizes that many kids feel restricted by their parents controlling their media use. Huss fostered a healthy conversation about online safety with her son, Mingus Allen ‘25, when he was entering seventh grade. She began the conversation by using anticipatory guidance, creating scenarios that could happen online and brainstorming solutions together so he could make good decisions when the time comes.

“Some parents feel overwhelmed by technology and leave their kids to figure it out on their own,” Huss said. “I always tell parents to start the conversation by asking their kids how social media works so they can learn enough to have an informed conversation. Building trust is more effective than using scare tactics.”

Kaiya S.’s ‘27 parents allowed her to use social media at the age of seven. Kaiya has never had a negative experience with social media, viewing it as a way to connect and share interests with her friends and others online. She practices online safety by checking if someone who has requested to follow her has enough mutual friends. Both her parents follow her account on Instagram, and Stormare has never felt that her parents have distrusted her.

“What made my parents’ approach so effective was that they set clear boundaries,” Kaiya said. “They were [also] honest with me of the possible dangers of using social media. With the boundaries my parents set, I learned early on to use social media safely”