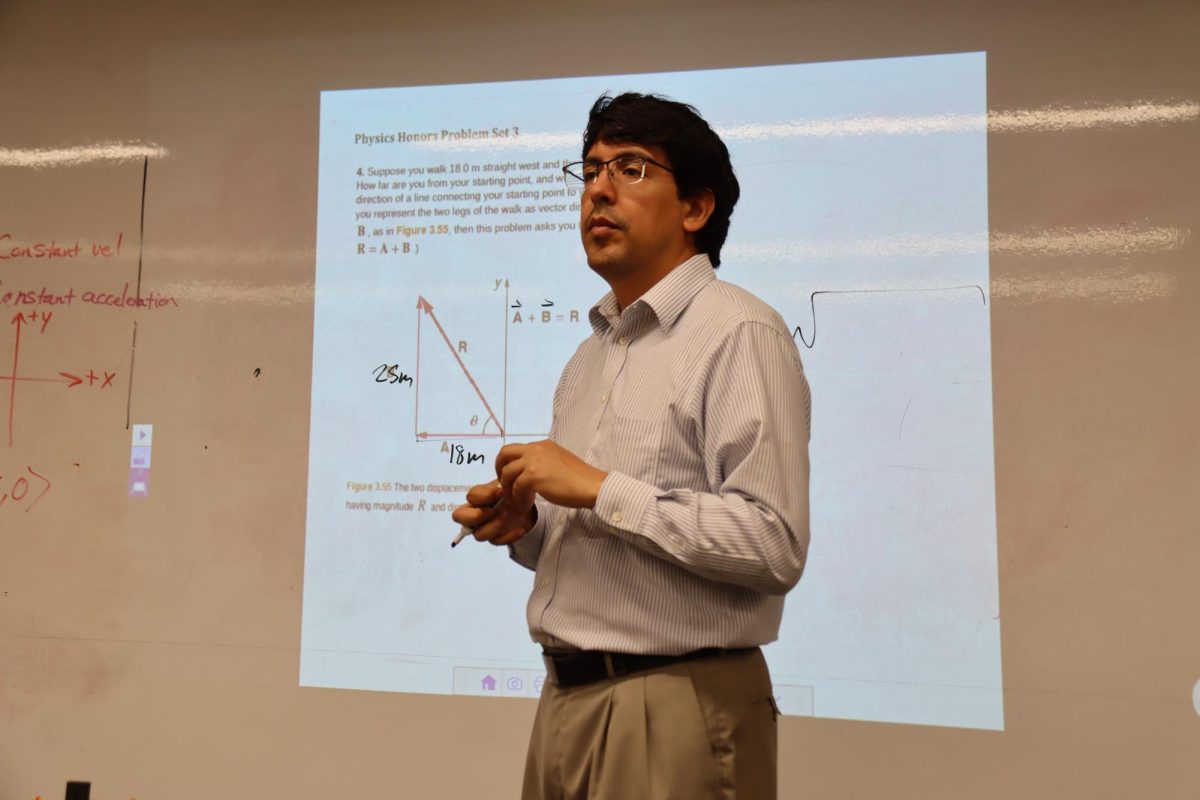

As Dr. Amanda Dye, high school science department chair, starts her class when she notices one of her top students feeling zoned and burnt out. Not having her students bring energy makes it difficult for Dye because now she has to be more enthusiastic for the class. After class she approaches her student and makes an effort to help by making a realistic schedule. They sit down together and decide what needs to be done now and what can wait to be done in terms of their workload.

Dye finds that these feelings of sadness, which lead to burnout, cause her students to conserve their energy for themselves, meaning Dye has to create enthusiasm for her classroom environment by showing more excitement and passion. She thinks that burnout is when one is so overwhelmed by their workload it becomes almost crippling, hence she mostly notices burnout in her overachieving students. Even though she has experienced burnout herself, Dye detects that student burnout is more difficult to manage than teacher burnout.

“Students [are] consistently having to meet these benchmarks [and are] consistently being assessed on [their] knowledge,” Dye said. “I do feel like because [students] are so dependent on this system [the way school runs], that [student] burnout is almost more difficult, because you have less choice. There’s only so many things you can manipulate in that [school] system. For me being a teacher, there are more things I can manipulate, [such as] if I’m going to talk more or less today, [or grade] this homework on completion or a grade; that choice is not there for [students].”

As someone who has experienced burnout in the past, Susanna J. ‘25 would define it differently from Dye. Motivated purely by her passion for learning, Susanna takes as many advanced courses as possible and notices that burnout happens when she loses sight of that passion. She finds that the main contributor of burnout occurs quicker when her efforts don’t result in a desirable grade.

“[I get this feeling] that there’s no point to everything I’m doing [when I get a bad grade],” Susanna said. “It’s not necessarily having too much work, because I’m always working hard, but when it doesn’t pay off as much as I had expected, it can be really discouraging. [Then], I question if all I’m doing is even going to matter in the end, or if I’m working towards a goal that’s not even going to be realized.”

Rather than feeling burnt out only from academics, Charlie L. ‘26 constantly feels burnt out when creating digital art. Setting milestone projects like creating one animated short film a trimester helps keep them motivated. They tend to notice burnout once completing an art project because Charlie’s perfectionism causes new artwork they create to seem unfinished to them. However, Charlie has learned how to combat burnout by using different mediums like sketching, film or collaging. They try not to let burnout phases affect their school work, but it tends to take longer because they no longer have an incentive to get schoolwork done when experiencing artistic burnout.

“I need to finish my homework so I can get to make my cool art stuff, but if I don’t feel motivated to finish my art stuff then I don’t feel motivated to finish my homework,” Charlie said. “But if I don’t even want to do that [art project], then I’ll never do this [homework]. My brain works on a reward system.

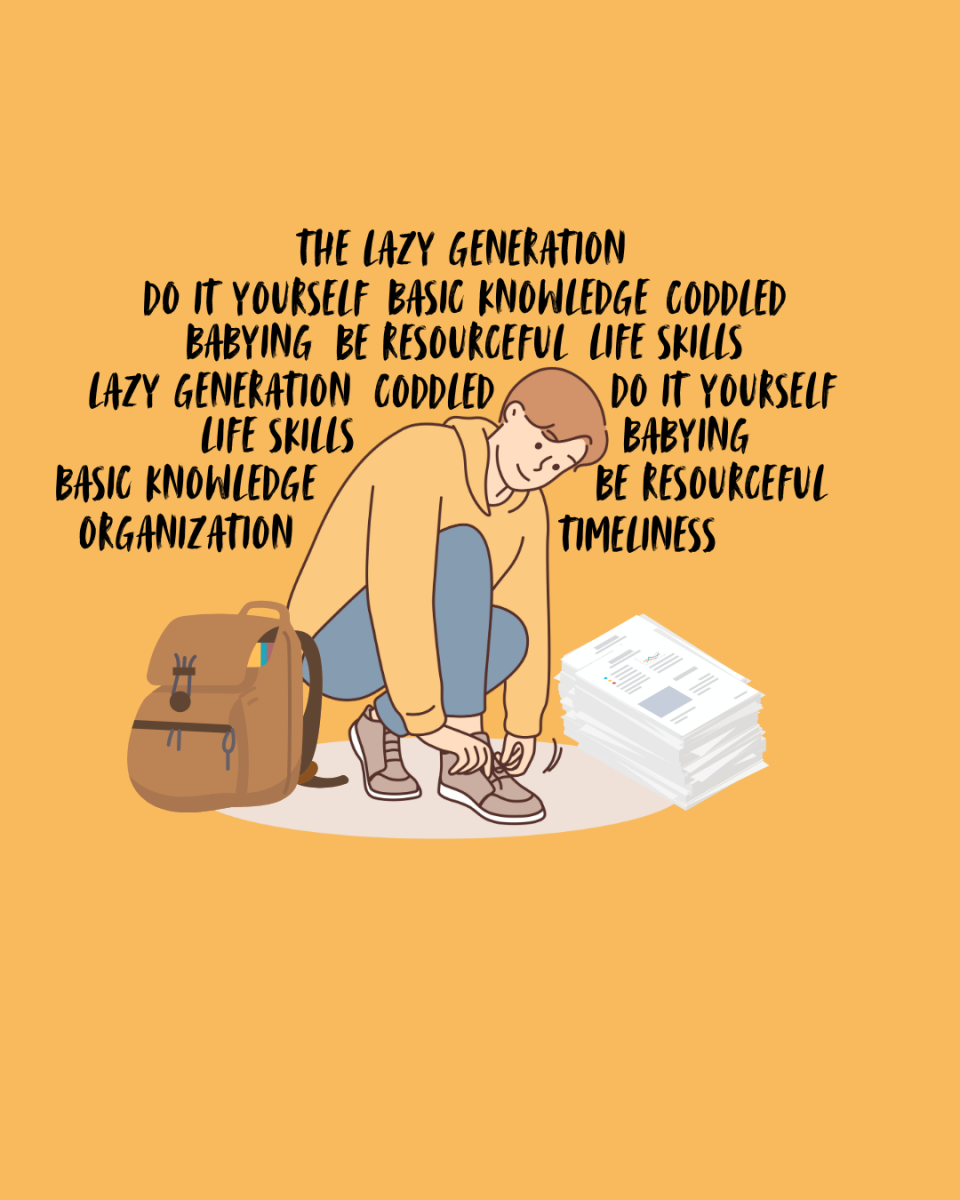

Eli R. ‘26, who is similar to Susanna with his rigorous academic schedule, doesn’t believe burnout should happen in high school, but nonetheless sees the benefits in it. He believes burnout occurs when his workload is particularly taxing, such as the end of a trimester. As a result, being burnt out means that Reyblat must sacrifice his sleep and his extracurriculars, such as cross country and working at Trader Joe’s. However, expects that experiencing burnout will give him experience he can take with him into university, where he plans to go into pre-med.

“I wouldn’t want the first time that I’m feeling burnt out to be in higher education when I don’t have parents, teachers and deans [to give me] support,” Eli said. “I think that would make the burnout later in life more manageable [because] it builds resilience. I always believe that the more you put on yourself, the more you can get done, [so even though] I don’t want to burn out, I’m glad that I [am] so I’m not shocked by the feeling [later].”

Similarly to Eli, ninth grade dean Dr. Leticia Sanchez sees burnout as a potential learning opportunity. As an educator for 20 years, both in high school and university, she has noticed that students feel responsible for their work to an overwhelming degree. She believes that, unlike adults, who have the life experience and awareness to know burnout will end, students can have little confidence in managing their workload and struggle to enlist support. However, she believes the lesson should come in knowing when you are about to experience burnout, rather than the burnout itself.

“I think part of the high school experience is learning how to identify when you’re feeling overwhelmed and learning how to ask for help in those moments,” Sanchez said. “The goal is never to push [yourself] until [you] burn out, and no teacher is [trying to] to push you until you [do]. [Teachers] don’t expect students to [experience burnout]; it’s not a normal part of student life.”